A runner's reprise

I don't know if anyone else feels this way, but there is a difference between being someone who runs vs. being a runner.

Or someone who likes photography vs. a photographer. Or, someone who does pottery vs. a potter. Or, someone who likes climbing vs. a climber. You would think that if you do it enough, you will start to take on its identity, but I haven't found that to be the case with running. I've run an ultramarathon (50K) but even then I've never identified as a runner. I used to run to cross-train for tennis, or to prepare for a triathlon, and in all those years I've probably run over 1000 miles, but never once did I think of myself as a "runner."

But for the first time in my life, I'm starting to... I don't know what happened, but there was a switch. I have a suspicion that it's because there is nothing else that I'm running for... other than to run. I'm not running to cross train for some other sport, to get a fitter body, nor to finish some race as fast as I can. All I know is that when I roll out of bed and put on my shorts and toe socks, I feel like a runner because of what I'm deciding to do with my time.

I'm trying to build the capacity to do the thing that I want to do most: enjoy 30+ miles of trail and nature without having to bring a backpack and a tent, or having to compete for an overnight pass from the ranger station. I just want to feel the leaves and branches whoosh past me as I'm surfing through a single track trail. I want to escape the oppressive, straight lines of civilization, and fly through a wildly drawn world. I want to be at some roaring river one hour, and be on a mountain pass the next. Simply put, I love the outdoors for the freedom, and the way I see it, more speed is more freedom.

Getting back into running

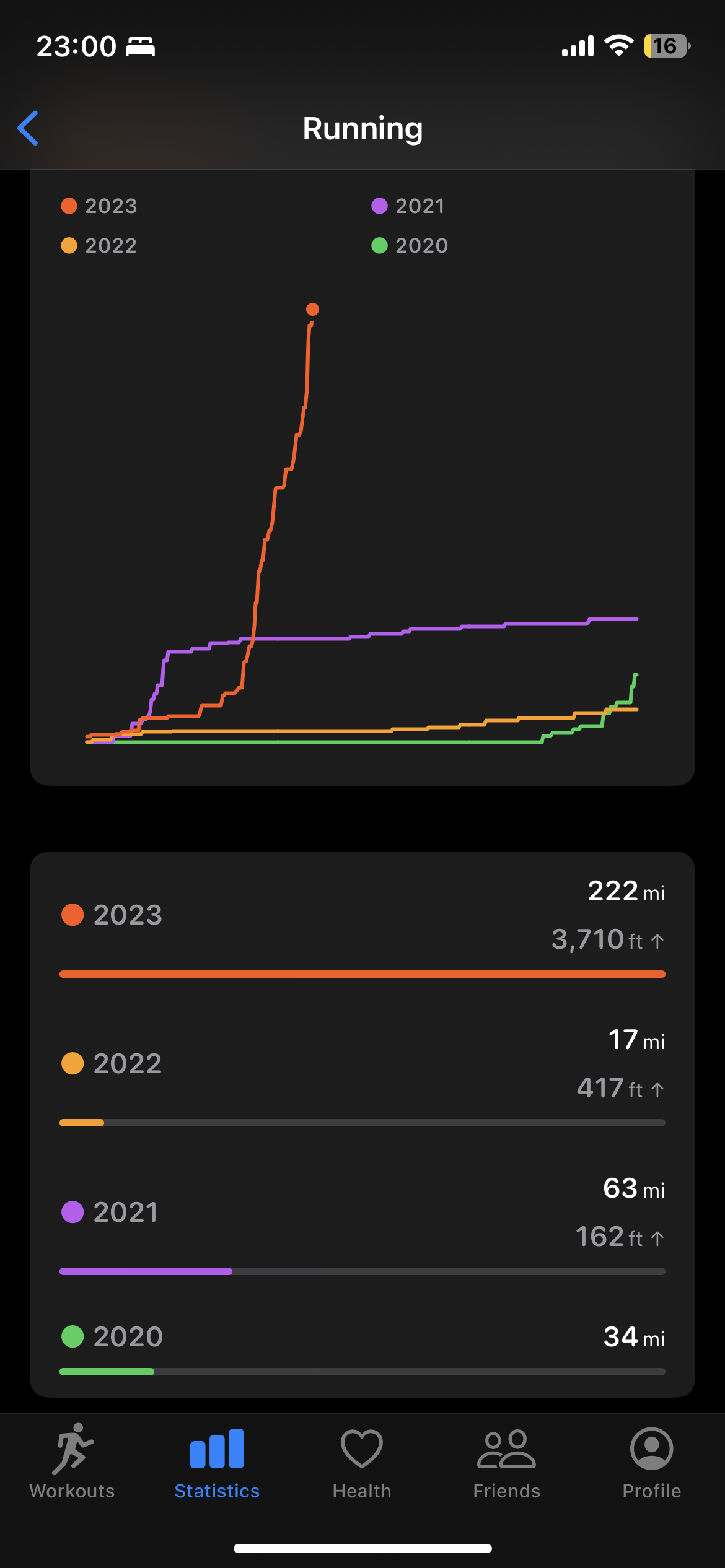

You should know that before I started running again, I hadn't run more than 20 miles a year. Look at the screenshot below:

Back in early 2021, I was confined by an ankle injury from frisbee. I used the injury to bury myself in work for the next 18 months (see yellow line above), instead of trying my hardest to rehabilitate it. I slowly got more sedentary, until it became harder and harder to get back into being fit again. I lost my sense of self as an athlete and an able-bodied person. I didn't know it at the time, but I became an unhappy person, largely because I couldn't do the things I that used to bring me so much serenity (e.g., long hikes, being in nature).

Fast forward to few months ago: I sprained my back playing tennis (twice in two months, actually!) and I noticed that the only times that my back felt better was when I was standing. And then (just to experiment) I noticed that a light jog completely eliminated the pain and stiffness. Slowly, and then suddenly, I just fell in love with running. I suspect that I had a very positive association with running because of both the normal running endorphins, and because it alleviated my back pain. I hated starting every run but I loved how I felt at the end.

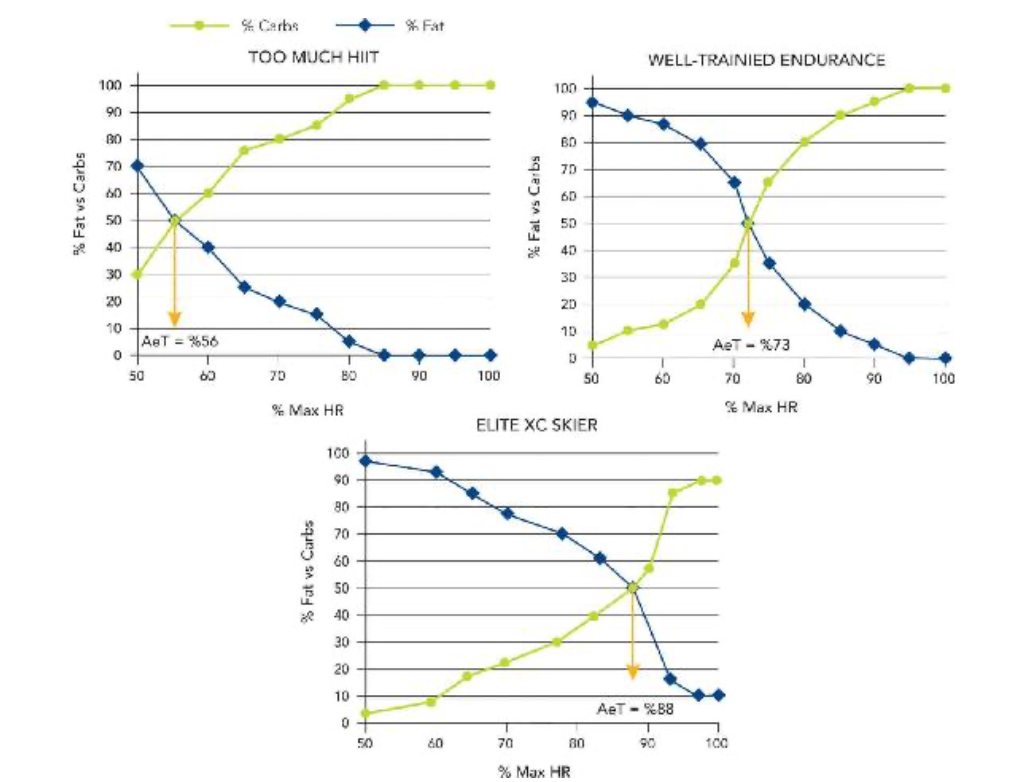

I eventually want to cash in all this running capacity to "run mountains," so I started reading Training for the Uphill Athlete by Steve House and Kilian Jornet, which completely changed the way I think about athletic training in general. They start the book by explaining endurance through a metabolic lens–more specifically, the physiological differences between aerobic and anaerobic exertion, and why it's important for long-endurance athletes to stay in aerobic zones: aerobic metabolism burns more fat as energy while anaerobic burns carbs (glycogen) as energy, and while there are 200,000 kcal of fat that we can tap into, there are only 2000 kcal of carbs in our liver and muscles we can tap. (When you run long enough and use up all your glycogen, that's when you start to feel like you've "hit the wall".)

But the most important takeaway from that book comes from these three graphs (below), where they compare the substrate utilization of three different athletes. At the same intensity level, endurance athletes can use more fat than carbs than a non-endurance athlete. This is metabolic efficiency. From a training perspective, I find it super cool to think that a body as a metabolic machine that can be tweaked. In the book, they say "endurance is a metabolic quality," which adds a whole new dimension to the way I think about my body as an athlete: it's mind, muscle, and metabolism! Being able to change which fuel my body can use for energy is like a cool hidden superpower!

Patience pays off

I have a hard time being patient with physical activities. I have a habit of too hard, too fast into a new hobby, and then I get some kind of injury (and my friends laugh because I keep making the same mistake). But now that I injured my back, I had a real reason to go slowly.

Uphill Athlete also taught me the importance of base training, and that if you don't have the proper aerobic base, then you shouldn't be doing any kind of moderate running until you do a LOT of really– really– slow runs (the book says until your aerobic threshold HR is within 10% of your lactate threshold HR).

I took the advice... and I've only been running for about 6 weeks (95% of it really slow) and there have been major improvements already! I've been focusing on running long, slow miles, tracking only my heart rate (target 130-142) and my cadence (target 180 spm), and for the first 4 weeks have been running at about 11:00 min/mile pace, with the injury. It took a lot of discipline to run this slow, but what's more important is that I log miles day after day. Slow running lets me avoid injuries and it helps me recover faster because I don't build up lactate.

At 6 weeks of training, after a second recovery week, I took my usual foundation run up the SF Bay Trail with a 137 bpm target, but this time my pace somehow improved so much I was starting to think my sensors were off. I was running at the same HR but now at a 9:00-9:30 pace. This is still relatively slow compared to well-trained runners, but consider the change after a month of easy workouts.

There is a huge life lesson that I'm going to be looking back to for years, and kind of ties into what professional ultrarunner Dani Moreno said at a talk she gave: "consistently good > occasionally great." It's so incredibly powerful to just slowly improve from gentle consistent work. You see it pay off eventually, even if it feels like nothing changing.

Change is happening... just trust (and love) the process.

P.S. if you want to start running, I highly recommend this short book of essays, I Hate Running and You Can Too: How to Get Started, Keep Going, and Make Sense of an Irrational Passion by Brendan Leonard, which you can read in about 3.5 poops.

@westleydang Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.